One of the last great heirs of modern culture and at the same time one of the great authors of the early Post-Modern era: Platform meets Mario Botta.

Luca Molinari | For our conversation and for this issue of Platform, I have chosen the term “classic,” which almost seems cheeky, because on the one hand you might well be considered one of the last great heirs of modern culture, certainly not least because of the masters you’ve had, and on the other hand you are one of the great names of the early Post-Modern period. Today, we relate to the modern movement and its legacy as a classic to be critically re-read.

Mario Botta | Yes, I’m very pleased with that.

L.M. | Shall we start with that? Because among the younger generations especially, not everyone knows your history very well. You were fortunate as a young person, you graduated with Carlo Scarpa and in Venice you worked on Le Corbusier’s hospital and then on Louis Kahn’s congress hall. After so many years, can you tell us what that moment meant for you as a young designer, and what still remains within you from that experience? What do you carry with you from Scarpa, Kahn, and Le Corbusier today, after all that time?

M.B. | Even today they are still three of the great masters that I had the privilege of meeting in Venice, in a pre-’68 atmosphere; I mention this in order to provide the political context. In 1965, Giuseppe Mazzariol invited Le Corbusier to take part in the hospital project. So, the first thing I thought to do was to write to Mazzariol, who was also my history of architecture professor and tell him that I couldn’t miss this opportunity, even though I was still in my first year of architecture. I insisted that I would go under any conditions. The reply I got was that I could forget about it because Le Corbusier did not accept students. He understood my position as a student coming from Switzerland, but it was not possible to contact him. Six months later, I received a note asking me to come to the Querini Stampalia Foundation because there was important news. I used to visit Querini Stampalia every day as the library remained open late for students, especially architecture students. I wasted no time and went there the next day. Mazzariol informed me that there was an opportunity to work for Le Corbusier, because Guillermo Jullian de la Fuente and José Oubrerie – two of the Master’s collaborators in Paris – were coming to Venice to set up a studio to talk with the hospital’s directors and establish the necessary project details. So, I told Mazzariol to suggest me as a studio assistant: I would unlock the doors, clean the floor, anything… That was how the first contact happened, with no demands; just with this stubborn desire to meet the Master and understand what his final project, which already seemed prophetic to me at that time, would be like.

The meeting with Louis Kahn took place in 1969 when Giuseppe Mazzariol tried to promote a project for the Congress Hall in Venice. In the same way as happened with Le Corbusier, I found myself again as a studio assistant, this time remotely, for Kahn. But, unlike Le Corbusier, Kahn came to Venice and stayed for an entire month during which I worked closely with him.

Last but not least, I want to highlight the importance of Carlo Scarpa, who mentored me for five years of study until he became my thesis advisor. Before being a great architect, Scarpa was a great craftsman; I consider him one of the last heirs of Renaissance culture. He could give shape and expression to even the humblest materials, and he knew how to bring out the beauty in everything he touched.

L.M. | It’s interesting that you mention Querini Stampalia, which was restored by your mentor Carlo Scarpa, and where you have been involved over the years as a designer. It seems like a fantastic convergence of destinies. I think that things never happen by chance.

M.B. | Let me share a little story with you. Before going to Venice, I had already done some work because I had been an apprentice for three years in an architecture studio in Lugano and as such, I already had some professional experience that improved my standing a good deal in Carlo Scarpa’s eyes. On the one hand, he liked the idea that I had already built things, and on the other hand, because I lived in Switzerland, he always asked me to bring him a special brand of cigarettes that were only available in Chiasso.

L.M. | Was that three-year period the one you spent with Tita Carloni? A somewhat underrated author but of great quality.

M.B. | Exactly. His studio was the most avant-garde in Lugano, and I owe a lot to the professionalism, atmosphere, and work that took place there. I was 15 when I started my apprenticeship; I had no cultural background, but I was immediately able to breathe in the passion and research that was within the origins of organic architecture. Carloni admired Alvar Aalto and Frank Lloyd Wright so much that when the latter died, he decided to close the studio for a day of mourning.

L.M. | I imagine that this atmosphere influenced your studio over the years. In short, you “drank at the fountain” but what is impressive, looking at the monographs of your early works these days, including the beautiful one curated by François Chaslin and Pierluigi Nicolin for Electa where your first works are showcased, is to see how, in the late 1970s, as a recent graduate, you started producing a series of single-family houses that are now impressive for their novelty. I remember the magazines of that time, but looking at them now, it’s impressive because you were going in a different direction compared to the ongoing debate in Europe. You emerged with works that were completely alienating, with a sense of strength, form, and geometry that clearly originated from the teachings of Kahn and Le Corbusier but were completely reworked by yourself with absolute innovation. I’ve always been curious about the reasons behind these choices. Why did you start producing these types of architecture? What pressure did you feel from within?

M.B. | It was the Romanesque, which was my first school of architecture and in particular, the Lombard Romanesque that abounds in Canton Ticino, where I grew up, and in the Italian border territories, and here I’m thinking of Galliano, Civate al Monte… Since I was young, I breathed the air of the Romanesque, and these were the primary reasons for my love of architecture. I studied architecture because I knew the Romanesque churches that fascinated me as a boy. The Romanesque identifies with the principles of construction. In the Romanesque, you feel the force of man opposing nature with extraordinary balance. And then there is the rigour, even geometric, but above all in the use of materials: a single material to build a church.

L.M. | It’s interesting because it’s as if you were talking about a contemporaneity of history in which you combine the Romanesque with Kahn’s geometries, which in turn drew inspiration from Roman and Romanesque architecture. In this case, the relationship between history and projects generates completely new forms.

M.B. | Yes, the example of the Romanesque, its power, and its allure for a young architect led me, in fact, to my work: a youthful infatuation not yet spoiled by formal education. Even today, it is difficult for me to distinguish the teachings of Romanesque architecture from the geometries of Louis Kahn.

L.M. | This was also because you have moved along a line of strong formal autonomy; if I look at the debate of the last thirty or forty years, your work has its own autonomy compared to the ongoing debate, reminiscent of the work of other contemporary authors like Ando and Moneo.

M.B. | To use a paradox that I really like, it’s the “richness of ignorance”. You don’t have to know everything to do our job. You need to know how to choose and invest a lot in certain things so that the complexity of architecture never ends, even though it has become increasingly virtual. Architecture, now, is more connected to the idea than to physicality.

L.M. | I find this is a central theme today. I was rereading a small text of yours on Louis Kahn that I really liked, where you talk about this continuous wear and tear of technological forces, already in 1999 about 25 years ago, saying that technology is now consuming matter to the point of dematerialization. But at the end of the day, as much as we want to believe that everything is dematerialized, at the end of this journey, there is a building made of flesh and bones, a real body.

M.B. | That works with gravity.

L.M. | Gravity is the other major element because architecture is born to counteract gravity.

M.B. | Yes, but gravity is still a constant in architecture today, which is nothing more than the organization of a living space for human beings. Every construction, by its nature, has weight and material that works with gravity. It’s an unescapable fact: even the most futuristic architecture ultimately finds its logic in putting loads on the ground. This conviction has stayed with me over the years, to the extent that even in my role as a professor, I have always tried to make students aware by asking them how things stand, how forces are discharged, loads, even spatial tensions. Media culture has hi-jacked the term “lightness” as a positive term, creating misunderstandings that also affect artistic practice.

L.M. | What you’re saying resonates with me a lot. Every time with my students, I try to explain how crucial the grounding of architecture is—the way in which a building rests on the ground is a design in itself. Indeed, great architecture always finds fascinating ways to connect with the ground, either by denying it, almost flying, or by effectively bearing its weight. It’s a beautiful architectural theme.

M.B. | Luca, if we’re talking about fascination, we should also think about Piranesi, who, let’s not forget, was also an architect. His lithographic “architectural” prints intertwine the idea of attachment to the ground with a spatiality made up of vaults, arches, and bridges. His art has inspired many other architects.

L.M. | For example?

M.B. | I think of Louis Kahn, who said fantastic things about the origin of a project, such as “the beginning already contains the whole.” With this insight, he meant that if the impetus – even an ideal one – of a work to be built is missing from the beginning, then it’s a false start. So, he warns us about static strength and intrinsic force, telling us that if we ask a brick what it wants to be, it says it longs to become an arch. And we come back to gravity: the bricks working against each other to become an arch. It’s a philosophically powerful intuition.

L.M. | It’s a wonderful image. By the way, speaking of great masters you have engaged with, starting from Ticino, another great one that I loved in your reinterpretation of San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane is Borromini. I’ll never forget that 1:1 scale model of the section of San Carlino, which, for me, is one of the most exciting things you’ve done—forgive me for saying so.

M.B. | Yes, it’s true, it’s true.

L.M. | That section you had floating on the lake, reminiscent of Aldo Rossi’s Theatre of the World, was incredible.

M.B. | It was a simulated floating because it was supported.

L.M. | Of course, no, it’s obvious.

M.B. | Aldo Rossi’s was even more lyrical; it truly floated. One of the ideas behind San Carlino was inspired by an observation by Carlo Dossi in his “Blue Notes”: “the dominant character of architecture is given by the context that strikes the artist’s eye.” With this phrase, Dossi warns architects that it’s not us who create the dominant character but the context. So, I thought that Borromini left Bissone, where he was born in 1599, to attend the school of the stonemason Andrea Biffi in Milan. This opportunity allowed him to work on significant construction sites, including the Milan Cathedral. Then he moved to Rome, where he was paid ten times more than other architects thanks to his impressive talent. One of his early works is San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane.

San Carlino in Ticino was created as a tribute to the four hundred years since Borromini’s birth, a way to explore whether there was a connection between the memory of the landscape experienced by the young architect and the reality of an architectural work referring to a specific context. Borromini was born and raised on the shores of the lake, where the mountains rise steeply, sometimes hanging over the water. The idea of interpreting the landscape as architecture confronting the geometry of the horizontal plane of the water provided the inspiration for San Carlino. I recall a statement by Rafael Moneo, who, during his visit to Ticino and after seeing our lakes, said he understood why our area had produced a generation of great builders who have worked worldwide (in addition to Borromini, think of Fontana, Maderno, Solari and Trezzini).

L.M. | But is it the same for your works?

M.B. | I wish it were so. Building a living space for humans—architecture—is an artifice compared to nature. It’s a way to indicate the transformations carried out by man, and precisely as an act of creation, it transforms a condition of nature into a condition of culture. These values build our identity and become part of our DNA. They are emotions and images of our experiences, the fleeting memory of metaphorical values which are sometimes stronger than technical and functional experiences. This is why the transformations brought about by architecture become fundamental parts of the human landscape.

L.M. | Certainly, it’s a synthesis, it’s like a synthesis between the two parts, like the synthesis that becomes form, which we then inhabit.

M.B. | Borromini left his hometown, and I like to think of him as my neighbour. Every day I think that he lived in that place and saw the same landscape I see. One must be a bit obtuse not to understand that the landscape can provide a strong stimulus for architecture.

L.M. | Earlier, you made some ironic remarks like the humble person that you are, saying you were fortunate to be ignorant. However, one thing you have often stated in your life and which has always struck me, is that you have always sought not only masters of architecture but also masters in other disciplines, such as art and literature. You’ve had many of these masters, and with some, the good fortune to make museums, like Dürrenmatt, for example. But you have always consciously sought good company, and for you, this is part of your design thinking, part of your journey.

M.B. | Yes, yes, yes. You mentioned Dürrenmatt, whom I had the privilege of meeting and establishing a friendship with his wife, Charlotte Kerr. Dürrenmatt was a fascinating personality who, through literary creation, ruthlessly delved into the precariousness of man, whose isolation and loneliness he paradoxically and grotesquely denounced. In my opinion, he represents the mark of culture within the contradictions of Switzerland.

L.M. | Ah, him, yes, he was amazing.

M.B. | He was a monster of talent.

L.M. | His books are beautiful.

M.B. | At the moment, I’m rereading the novel “Il Minotauro,” a reimagining of the classical myth. Here, the Minotaur is a sensitive being forced to live in a labyrinth made of infinite mirrors, each representing illusions of itself.

I also think of Max Frisch, who, unlike the rigorous and agnostic Dürrenmatt, was a romantic, a novelist, and a playwright whom I admired for his writings and also for his architecture. What has always intrigued me about him is that he downplayed his work as an architect, almost as if literary perspective surpassed his architectural critical ability.

He had the habit of taking his literary friends to construction sites. One day, he brought Bertolt Brecht on a visit, an experience he described in “Diario d’antepace.” Brecht was not the writer trying to interpret reality through ideological filters; he was a man of contrast, confrontation, and critical dialogue. He was precise even in technical observations, asking Frisch about the purpose of a staircase or a window. The staircase, Frisch replied, serves to create a relationship between the condition of an artificial plane and nature, and the window allows a view of the lake. In fact, Brecht was right: the architect Frisch had erred in both the staircase and the window. So, at a certain point, Frisch told Bertolt Brecht not to visit him anymore, pointing out that those who go to see another’s work often find errors.

L.M. | Yes, because the perspective changes, because each author looks fixedly at what they do, as they are immersed in it, while another with a lighter approach sees things you no longer see.

M.B. | Yet it’s interesting that Brecht latched onto Max Frisch’s errors.

L.M. | And have you had any Brechts in your life who have caught you out?

M.B. | Many Brechts, because my work is in plain sight of everyone, and I have had the privilege of being around great critical minds, each in their own field. Returning to Dürrenmatt, his naïve gaze always impressed me to the point where he stated, “I paint like a child, but I am not a child; I paint for the same reason I write, because I think.”

L.M. | That is indeed so, but this idea is interesting because naïveté is a form of protection from the world, isn’t it? And also, the idea of looking at things in a different way each time as if they had never existed before. That is a wonderful thing.

M.B. | This is a prerogative of the greats, isn’t it?

L.M. | I don’t know, but perhaps we should all try to look at the world in this way, don’t you think?

M.B. | Yes. It would be beautiful to always see it with different eyes and be amazed every time, letting go of everything that is not essential.

L.M. | I understand that there is also the theme of reality, but finding things to fall in love with in reality every now and then is still important today, I believe.

M.B. | Yes, very important. For example, I think I’ll owe Dürrenmatt for quite some time because every time I reread him, I discover aspects that may well have escaped me.

L.M. | Yes, it’s like rereading architecture every time and asking different questions. I am convinced that every time you see a work by Le Corbusier, you ask new questions because you look at him with a different approach. Mario, I’ll ask you one last question because I don’t want to steal too much of your time, but what are the latest projects your studio is working on right now? We’ve talked about various stories, but your studio continues to work; now you have partners, so it’s a studio that is also working with the new generation.

M.B. | No, we’re not partners, but my three children work with me.

L.M. | But what are you working on these days that excites you?

M.B. | Well, it’s a very challenging period. I’m working on old projects. In Korea, a large church is under construction – it will be inaugurated this year – and it has taken up a lot of my time because it’s not just a church but a piece of landscape; it’s like a dam at the end of a valley, and the city develops below the dam. It’s as if I’ve connected the two sides of the valley. Then, I’m overseeing another major project in China, where I’m building a university campus in Shenyang, a city north of Beijing. It’s a campus for the Academy of Fine Arts founded by Mao Zedong in 1938. Initially, they asked me for a masterplan, but later they told me I had to build everything.

L.M. | I saw your project at Tsinghua University in Beijing a few years ago.

M.B. | Next week, the new president of Tsinghua University, for which I have not only built the museum you saw but also a library, will visit me in the studio. You know, working in China is very difficult. During the construction of the museum for Tsinghua University, three groups of a hundred architects each were working for me on-site, while here I had only three collaborators! Suddenly, I found myself having to oversee three hundred architects who sent me countless drawings to correct.

But they’ve become clever too. In Shenyang, they came up with a trick when I asked them for some photographs: they send me aerial shots to give a better view of the campus, but each time they go higher and higher to take pictures, so the details become invisible; it’s like seeing a real master plan. Things have also stopped there; the world has changed there too.

L.M. | Yes, the city is changing a lot.

M.B. | No, I was referring to the pandemic. Covid has changed the world, and for two years, China came to a halt, shutting everything down. It’s only recently that they started up again.

L.M. | Mario, thank you very much. It’s always a pleasure to talk to you.

M.B. | I’ll be here waiting for you again. Thank you to you, and look, now you’ve become my accomplice, maybe you don’t know…

L.M. | We’re partners in crime, as the Americans say.

Text by Luca Molinari

Captions and Photo credit (from top to bottom)

– Mario Botta Portrait – photo by Flavia Leuenberger Coppi

– Mario Botta in his office in Mendrisio, Switzerland – Ph. Claude Dussex

– Mario Botta with Louis Kahn. Venice, 1969 – Ph. Botta Archives

– Mario Botta during the discussion of his degree thesis. Venice, July 1969 – Ph. Botta Archives

– Mario Botta with Jullian de la Fuente. Venice, 1966 – Ph. Querini Stampalia Foundation,Mazzariol Foundation, Martina Mazzariol

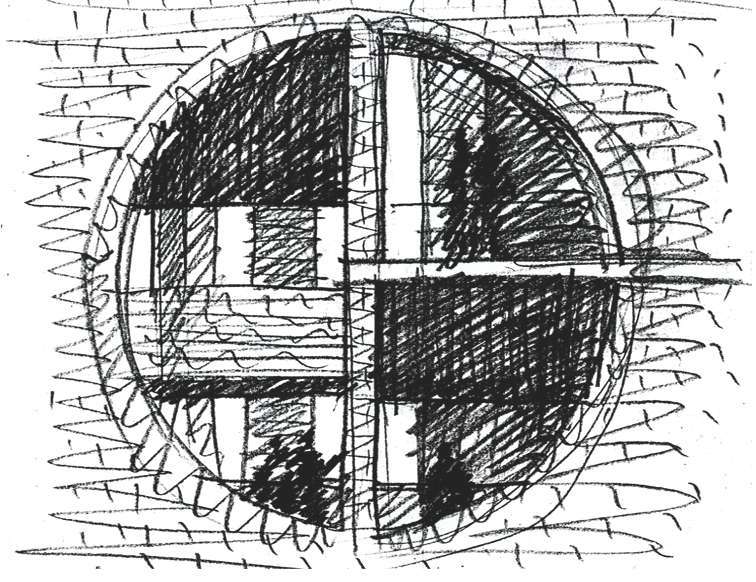

– San Carlino, Lake Lugano waterfront, Switzerland (1999-2003 dismantled). Preliminary sketches

– Church of San Giovanni Battista in Mogno, Switzerland (1986-1996). Sketch of the transversal section

– Detached house in Cadenazzo, Switzerland (1970-1971). Sketch of the opening

– MART – Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Rovereto, Italy (1998-2002). Sketch of the covered square

– Detached house in Origlio, Switzerland (1981-1982)

– San Carlino, Lake Lugano waterfront, Switzerland (1999-2003 dismantled) – Ph. Enrico Cano

– The Dürrenmatt Centre in Neuchâtel, Switzerland (1992-2000) – Ph. Pino Musi

– Detached house in Cadenazzo, Switzerland (1970-1971) – Ph. Alo Zanetta

– Church of San Giovanni Battista in Mogno, Switzerland (1986-1996) – Ph. Pino Musi

– MART – Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Rovereto, Italy (1988-2002) – Ph. Enrico Can

– Detached house in Origlio, Switzerland (1981-1982) – Ph. Lorenzo Bianda

– umanities and Social Sciences Library, Tsinghua University Campus, Beijing, China (2008-2011) – Ph. Fu Xing

– Tsinghua Art Museum, Tsinghua University Campus in Beijing, China (2002-2016) – Ph. Enrico Cano

– Interior of the Church of San Rocco in Sambuceto, Italy (2006-ongoing) – Ph. Enrico Cano

– Church of San Rocco in Sambuceto, Italy (2006-ongoing) – Ph. Enrico Cano

Click here to buy the new issue of Platform Architecture and Design